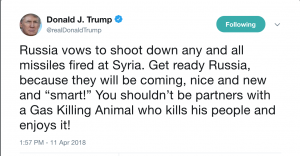

Last week, I posted my article on just war and the ascendance of foreign policy hawks in the White House on the same morning President Trump tweeted this:

Two days later, President Trump, along with his British and French counterparts, ordered a limited missile strike against the Assad regime in response to its alleged use of chemical weapons against civilians in the town of Douma. The Western powers launched 105 cruise missiles against alleged chemical weapons facilities controlled by the Syrian government. A week later, how should we evaluate this military action according to the just war tradition?

Let me begin by anticipating one objection: a onetime strike does not a war make. Sure, but launching over a hundred cruise missiles into another country is an act of war. This is especially the case when the attack is launched amid that country’s current civil war, one in which multiple nations are taking part either directly or by proxy. Christians should be concerned to evaluate even limited strikes—acts of war—according to the standards of just war.

What makes warfare just? Last week I quoted Bruce Ashford’s concise summary of what constitutes a just war, and it’s worth revisiting:

“A just war must have ‘just cause,’ meaning that it is defending against an unjust aggression. It must be initiated by a competent authority, as a last resort, with reticence, and for the purpose of restoring peace. There must be a reasonable hope of success and the anticipated success must be worth more than the anticipated costs.”

Let’s evaluate the latest Syria strikes according to these six criteria.

Just Cause

The use of chemical weapons against civilians is evil and could be a just cause for military action. On the surface this strike appears to be justified, and that is certainly what our government leaders would have us think. But, do we know for sure the Assad regime is responsible for this chemical attack? I know we were told that, but is being told the same as knowing? Peter Hitchens pointed out that all the initial journalistic reports on the incident—the very reporting that assured everyone that Assad was to blame—were filed from a distance. The closest report came from Beirut, while others were from Istanbul or as far away as London and Washington, D.C. Reasons exist to question the conventional wisdom. Why would Assad, who was on the verge of defeating the jihadi rebel groups, do the one thing that would provoke American intervention? Why is it not suspected that Jaish al-Islam, the jihadi group that held, but was losing, control of Douma could have been responsible for the attack? They allegedly used chemical weapons against the Kurds in 2016. Why was the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons been denied access to Douma for over a week? Why is it that some Douma residents do not even believe there was a gas attack? Of course, it is possible these are just Assad stooges who doubt the attack, and, thus, we are not to believe them. But that raises the question: whom are we to believe? Why do we assume Jaish al-Islam is telling the truth? Or, for that matter, why do we assume the war-happy foreign policy hawks of the Republican Party are telling the truth? Did we attack the group responsible for the chemical weapons attack—or did we aid them?

We do not know. And our lack of knowledge casts doubt upon the justness of our cause.

Competent Authority

The U.S. military, under the command of the President and as the defense arm of a recognized government, is a competent and legitimate authority. But our political system is governed by the Constitution, which requires congressional approval to go to war. The fact that presidents have routinely ignored this constitutional requirement for decades, with no consequence at all, does not make it go away. By failing to receive congressional authorization for these strikes, it seems that proper and competent authority was circumvented in this case. Of course, we did act in concert with international allies—the U.K. and France—and this is generally a good thing. International consensus is a bulwark against rogue military action, and multiple competent authorities agreeing on the justness of a cause strengthens the case for war. However, if we circumvent our own internal laws, even to act in concert with other nations, we are acting in bad faith and violating the competent authority component of the just war tradition.

Last Resort and Reticence

It’s quite difficult to view this strike as a last resort when it is still unclear who actually perpetrated the chemical attack and when it was not brought up before Congress. It appears a military response was the default option, with the only question being the scale of the intervention. However, I do detect some reticence on behalf of President Trump. He campaigned on a non-interventionist platform, and, despite recently stacking his foreign policy team with neoconservatives and hawks, one has to believe those instincts still carry significant weight in his decision-making process. His address to the nation on the night of the strike made clear his reservations about American military intervention in the Middle East:

“America does not seek an indefinite presence in Syria, under no circumstances … No amount of American blood or treasure can produce lasting peace and security in the Middle East.”

Purpose of Restoring Peace

I grant the Assad regime is monstrous and wicked. But what reason do we have to believe that toppling his regime will lead to lasting peace? Saddam Hussein’s regime was likewise wicked, but removing him led to more chaos than peace. Iraqi Christians, for example, have been routinely attacked by the jihadi groups that emerged in Hussein’s absence—just the type of rebel jihadi groups our government is currently backing in Syria. Just like we once backed Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan. When has our middle eastern meddling produced peace?

Success

Did we have reasonable hope of success, and was that anticipated success worth more than the anticipated costs? Define success, please. Considered narrowly, yes, we had reasonable hope that these limited strikes would be successful. We could destroy the alleged chemical weapons facilities fairly easily, with few casualties. But considered more broadly, what does success in Syria even look like? What are our national interests and objectives? What is our end game? I’m unsure anyone even knows, which makes measuring success that much more difficult (and makes perpetual war that much easier). For my part, I commend John Zmirak’s Switzerland option for peace in Syria as a worthy goal.

Conclusion

General Mattis described this strike as a one-time shot, and for that I am thankful. This situation had the potential for a more involved interventionist response, and I am glad President Trump resisted that temptation. Still, judging this act of war by the standards of the just war tradition, even this limited action was not justified. However, we have been so conditioned by an odd cocktail of perpetual war and sentimentality that we couldn’t even imagine not acting militarily. To quote President Trump, that’s “sad!”