By Levi Secord

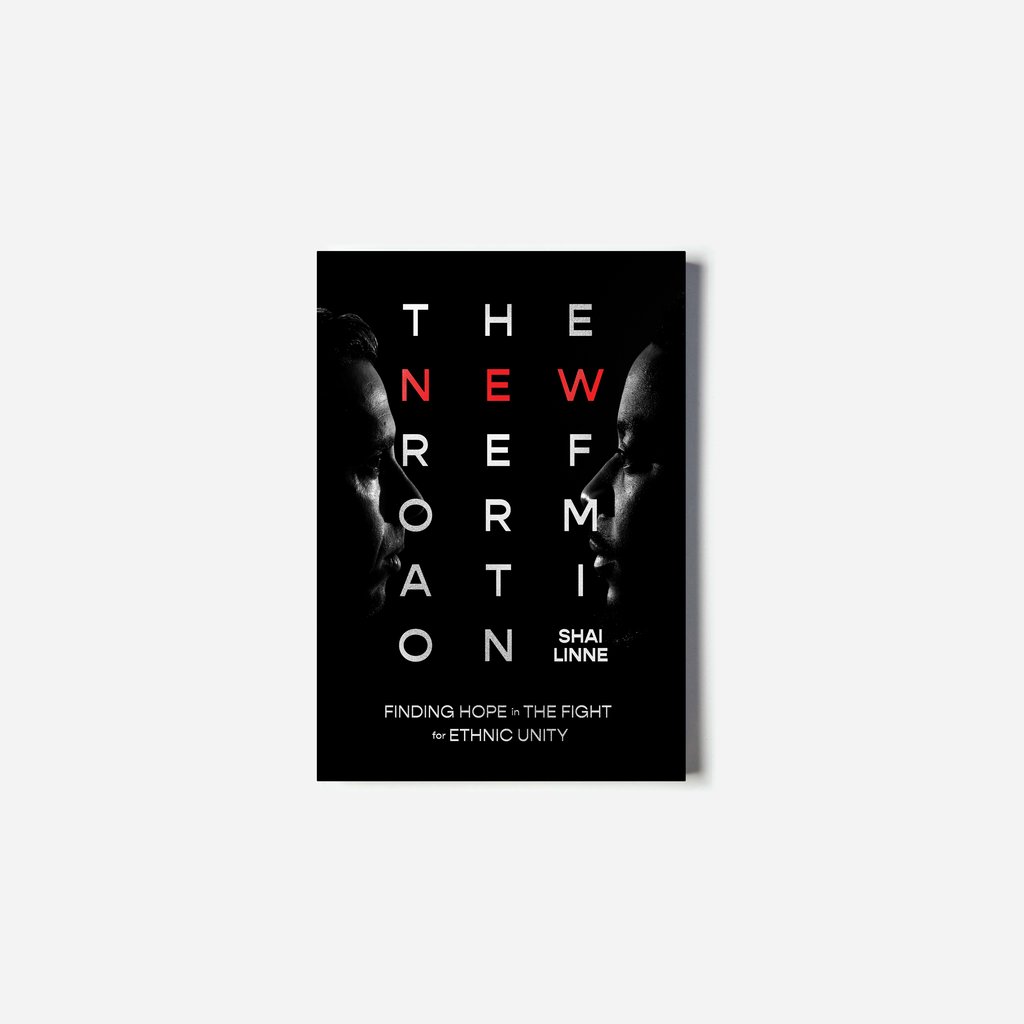

Recently, I’ve seen many positive comments about Shai Linne’s new book, The New Reformation: Finding Hope in the Fight for Ethnic Unity. Some portrayed it as a third way between the extremes of the woke and the anti-woke crowds. Naturally, such comments caught my attention, and I ordered a copy. As a pastor, writer, and father, I hope that God’s truth would dominate this discussion and that we would win over many of those in the middle, resulting in a stronger and more unified church. In his book, Linne attempts to be both biblical and balanced in his critiques and solutions. Largely he is successful, but there are some glaring missteps along the way.

The Good

This book is broken up into various sections, and Linne starts with his backstory and conversion. His conversion story encouraged me as it reminded me of God’s sovereignty and power. I was genuinely blessed to see the power of God and his sovereignty as displayed through the life of Linne.

Later on, Linne addresses some of the meat of the discussion, especially what Scripture teaches. For example, in very Voddie Baucham-like fashion, Linne rejects the terms “race” and “racism.” He writes, “This may seem audacious, but I believe that a big step in addressing this issue is changing how we talk about it. Words matter. The terminology we choose can be either helpful or harmful…Over the years, I’ve found the terms “race” and “racism” to be a hindrance in this regard” (16). My reply to this is a hearty, “Amen.” Instead of race, Linn endorses the biblical category of ethnicity.

Linne also affirms the authority and sufficiency of Scripture in dealing with our ethnic issues (104). Again, something I strongly endorse. In laying out his interpretation of biblical doctrine, I found more I agree with than not. For example, “The key to addressing ethnic disunity in the church is the proper application of justification by faith alone” (138). Linne places Reformed doctrine as central to healing the divisions that exist today. Salvation has nothing to do with our works or identity but is wholly a grace of God given through faith. Thus he rightly stresses that all people, regardless of ethnicity, are united in Adam as sinners and can be united in Christ by grace through faith. This truth is the only path forward.

Another strength is that Linne is not afraid to rebuke those who seek to weaponize “Blackness” and who have a bent toward wokeness. He writes, “But God forbid I ever toss Jesus to the side for the sake of “Blackness.” And God forbid I toss my White brothers and sisters in Christ to the side in some misguided attempt to prove my authentic Blackness” (150). Then again, “It’s far easier to dismiss someone as a ‘racist’ than it is to love them enough to consider their genuine concerns” (180). These are all praiseworthy and biblical.

Linne appears to be genuinely wrestling with this topic from the biblical text, and for that, I am grateful. I could have fruitful discussions with him about this topic because he is more concerned with truth and biblical fidelity than advancing the social justice agenda. Sadly, this reality does not mean the book is without its issues.

The Missteps

Linne rightly points to Christian unity as he writes, “But in Christ, there’s a new ‘we’ that supersedes every previous group we once identified with” (189). This statement is wondrously true, but Linne fails to consistently apply it as he often slips into pitting white Christians against black Christians. In particular, his chapter, George Floyd and Me, contains many such inconsistencies. Here are some examples:

It’s about the exhaustion of constantly feeling I have to assert my humanity in front of some White people I’m meeting for the first time, to let them know, “Hey! I’m not a threat!” (218)

And it’s about sometimes feeling like some of my White friends aren’t that particularly interested in truly knowing me—at least not in any meaningful way that might actually challenge their preconceptions. (219)

My fear is that the attention garnered by the protests will eventually die down (as it always does), and then my White friends will go right back to “life as usual.” (220)

What happened to the “we” that supersedes our old identity groups? Where is Linne’s biblical conviction that “We regard no one according to the flesh” (190)? On the one hand, we cannot champion ultimate unity in Christ and then, on the other hand, continually magnify divisions and judgments over ethnic lines. Many times throughout the book Linne falls into assuming the worst of his white brothers. It reminds me of what Pluckrose and Lindsay warn about in Cynical Theories, “If we train young people to read insult, hostility, and prejudice into every interaction, they may increasingly see the world as hostile to them and fail to thrive in it” (132). CRT and its pervasive influence cripple any attempts at reconciliation and unity as it trains many to prejudge others and to expect victimization. To be fair, at certain points in the book Linne pushes back against his own prejudices.

Another issue that Linne appears to unwittingly fall into is some of CRT’s definitions of justice and oppression. In describing ethnic oppression, he references the “mass incarceration of Black men in America during the ‘War on Drugs’” (115). His argument assumes that higher rates of imprisonment are automatically a sign of injustice: unequal outcomes are a sign of oppression. Such an understanding is at the heart of the social justice movement and the search for equity. To be clear, unequal outcomes can be the result of oppression, but we need more than just incarceration rates. Moreover, we would need to prove that many of these people were wrongfully imprisoned because of their ethnicity. Linne even compares this “oppression” to Israel’s bondage in Egypt and their suffering at the hands of the Midianites (115). To me, that is a giant and unwarranted leap.

While there are other issues that I could address, there is one remaining issue that needs mentioning—Linne’s silence on our specific concern about wokeness. We believe that these ideologies, like CRT, are unbiblical. If they are, we cannot look away and just seek unity. If social justice warriors are teaching evil and calling it good, then we cannot simply agree to disagree. We must find some clarity on this issue, but Linne never really addresses the substance of this disagreement that forms the heart of our current divide.

For this reason, the book remains largely unhelpful to our current divide. Linne’s description of the division, and his proposed middle ground, shows a certain level of ignorance of the debate. He writes of the two sides:

Satan is crafty, and he specializes in tempting Christians to distort two complementary truths by focusing on and disregarding the other.

So, on the one hand, he’ll tempt some believers to say, “What’s all this social justice stuff? Just preach the gospel!” Doing justice and preaching the gospel are both biblical imperatives (Mic. 6:8; Prov. 21:3; 1 Cor. 9:16). When they are pitted against each other, the byproduct is Christians that follow in the steps of the Pharisees… On the other hand, he’ll tempt other believers to get so consumed with earthly justice that they lose sight of the certainty of divine justice (Nah. 1:2-3), forgetting that God is both just and the one who is able to justify the oppressed and the oppressor through faith in Jesus Christ. May the life, death, and resurrection of Christ be the thing we shout the loudest even as we rightly give voice to its implications. (193)

The two sides of this debate, according to Linne, are those who only want to preach the gospel and fear that concerns about justice misplace it, versus those who are too concerned with earthly justice. This alignment allows Linne to settle himself nicely in the middle by making the gospel paramount and by highlighting its necessary implications. Linne’s assessment of the divide wholly misses the mark.

People on my “side” of this debate are not primarily concerned that the social justice movement cares too much about justice but that it cares too little about how the Bible defines justice. The work of Voddie Baucham, Samuel Sey, Neil Shenvi, Owen Strachan, and Darrell Harrison constantly argue, not that the gospel is being displaced by true justice, but that social justice warriors redefine and pervert justice. The concern is the baptism of injustice into Christianity in the name of social justice. This argument must be reckoned with if we desire to make any progress. The two sides are arguing for two different definitions of justice. They both can’t be right.

For example, the Bible teaches impartiality is necessary for justice, but CRT argues impartiality is unjust. There is no middle ground. Either we are right in our understanding of Scripture or not. Either the social justice movement is contrary to the gospel, or it isn’t. Linne fails to address the heart of our current divide, which significantly weakens his book’s importance.

Conclusion

While there is much to praise about Shai Linne’s book, ultimately, it does nothing to move us forward in our current divisions because it ignores the main arguments of the two sides. I believe that Linne and I, if we were to sit down and talk together, would share many of the same convictions and that we could perhaps bring more clarity to issues of ethnic tension, social justice, and critical race theory. But his call for a “new reformation” cannot happen without clearly addressing the doctrinal issues at hand. Our unity is found in substance, not unity itself. Ultimately, it appears this third way is more about ignoring the issues over competing definitions of justice than it is about bringing actual unity. If we are to make progress on this, Christians need to define what justice is, and just as importantly, what it isn’t. Until we do that, nothing will change, and there can be no “new reformation.”

Levi J. Secord serves as the pastor of Christ Bible Church in Roseville, Minnesota. He earned a Master of Divinity from the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary where he is currently pursuing a doctoral degree. Levi, his wife, and their four children live in St. Paul, Minnesota, where they spend their time slaying dragons.

Click HERE to subscribe to our Fight Laugh Feast quarterly print magazine!

5

1